ANGELS AND THE SPIRITUAL IN ABSTRACT ART.

A word of explanation.

The theme of angels in relation to the Buddhist-Hindu concept of Yakshas, or spirits of the vegetation, has been associated with New Age movements like the one that evolved at Findhorn. I have personally found the ideas of the theologian Margaret Barker and what she has to say about “Temple theology” very interesting. The basis of her Temple theology is summed up in the following way: “Temple theology traces the roots of Christian theology back into the first Temple, destroyed by the cultural revolution in the time of King Josiah at the end of the seventh century BCE.”

Personally I am very interested in Sacred Space, and how concepts of space have informed the spiritual art both in the Celtic and Syrian Christian tradition which we find in South India. The image of the Temple space has played an important part in imagining the relation of Heaven to Earth. The Temple is a microcosm, and this becomes itself an image of the “Heavenly Hierarchies”, which we find described in great detail by theologians like the Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, also known as “Pseudo-Denys”, who was a Christian theologian and philosopher of the late 5th to early 6th century. His great work on the ‘Heavenly Hierarchies’, and also on the ‘Names of God’, provided the middle ages with a basis for many of the masterpieces of Gothic art, like at Chartres. But he was also a theologian who laid the foundation for an ‘apophatic’ spirituality, that is a recognition that God ultimately is beyond all names and forms, and that the images we create are only our effort to embody an intuition of reality which is outside the domain of rational and discursive thought.

It is in this sense also that I would like to understand the angelic world as essentially abstract, or what in India is known as “Nirguna”. It was this intuition that was reinforced in my mind when I was asked to attend a small workshop of seven artists, brought together in the locality of Chorin, which is about 50 km from Berlin towards the Polish border. There, near an ancient Cistercian monastery which was founded about a thousand years ago, we were asked to give expression to our image of the ‘spirit of the place’. These pictures were later exhibited at this archaeological and tourist site.. The present ruins of the Chorin Monastery is a popular tourist attraction, and many concerts are held in the restored Church building which is itself like a musical instrument, in that it has wonderful acoustic richness. This brick built Gothic architecture became a model for a German understanding of its ancient Gothic style, which inspired a romantic idea of the ruin as a symbol of a spirituality rooted in the landscape.

While in Chorin I was shown a book containing many of the prints which Paul Klee made around the theme of the Angel. Important for him also was the image of the ‘Angel of Death.’ The following images are only an introduction to what could be expanded as an approach to the image of the Angel that points to the future of our planet earth. It is in this sense I have also tried to represent the ‘Angel of Ecology’.

Elijah:- "The Sun of Righteousness" (The Light of the world) shall arise with healing in His Wings, just before the Last-Day (Sura 43:61). Malachi ch. 4

An important aspect of the iconography related to Angels, is the symbolic importance of wings and flight. This includes both the idea of crossing boundaries, but also light, as the ancient image of the sun that we find in Egyptian art is of the Sun with wings which represent the rays of light. In the series of drawings which I did for the book of reflections written by Dr. Eric Lott on the healing works of Jesus, which he entitled “Healing Wings”,I used the image of the white goose, or swan known in India as the Hamsa, which is also related to the spirit, and to light (the Hamsa is nearly always shown as the finial of the Indian standing lamp.) The white wild swan is also very important in the Celtic tradition, and some have referred to the Angel as having “Wings of Desire” (for example the film by Wim Wenders, in the English version of the “Angel over Berlin”.)

In the art of the East, mythical birds like the Phoenix, or the Garuda, or Simurgh in the Persian Sufi parable, the winged creature is not only a messenger, but also a spirit that longs for the limitless, and searches beyond the bounds of human knowledge. It is this search for the Truth that crosses over cultural differences, which I feel is an important aspect of our present interest in the primal figure of the Angel.

Angels and the cosmos of Faiths.

I have been looking at the book on Angels by Jane Williams (2006). Introducing the subject of Angels, she writes : “Angels feature in all religious traditions, and people of different ages and different faiths or no faith at all have encountered them”. In Germany I found that many people are interested in Angels, perhaps because there is a kind of mythical element in angels, and they seem closer to our world than "God" which seems so abstract. In fact I think in the ‘Kabala’ it was thought that it was the Angels, rather like Wisdom, that represented the energies of God, working in nature. It was an Angel that was present in the Burning Bush, for example. It would be interested to know what Theologians think about the significance of Angels for today. In India, I have been in contact with a theologian who has interpreted the Book of Revelations in the light of political movements in a country facing Justice as well as ecological problems. What is important about our concept of the Angel, is that these spiritual Beings are inter-faith, representing a deep need in all cultures to respect the Spiritual powers and principalities that guide our political decisions. Angels have a very important place in the Islamic tradition, and we also find similar Beings in Hindu and Buddhist myths and legends. We can find a deep sense of angelic presences in the primal world of folk traditions.

Personally I have always had a devotion to Angels, and it is this angelic world that helps me as a Christian, in my encounter with those spiritual forces and symbols that mean so much to me in other religions. I feel that an understanding of the angelic can help us approach inter religious dialogue in an intuitive, and spiritual way. Angels are messengers, and in that sense they cross boundaries, reaching out to all cultures, and peoples. It is in this sense that angelic beings have featured in many of my own paintings. I would like to introduce some of these images, and what gave rise to them in the following brief reflections.

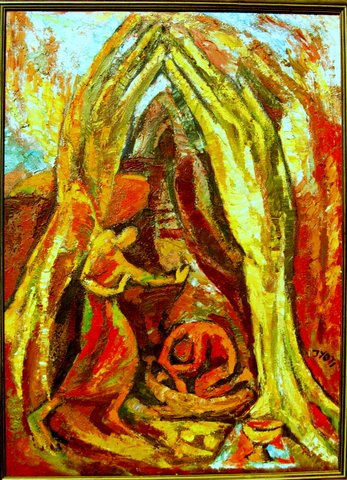

1. Dance in the Furnace.

This picture represent the “Fiery Furnace” that I find an evocative image. Perhaps the Furnace could relate to culture as a whole. Here, in a Mandala form, I thought of the movements of the body that are part of a series of gestures that are known as the ‘Surya Namashkar’, or greeting to the morning sun. This cycle of yogic postures are linked to the forms that we can find also in classical Indian dance movements. Traditionally the angels are thought to be spirits that continually dance before the Creator, in an eternal circle dance of light and joy. One could almost call this dance the ‘Yoga of the Angels’. In that sense the Angels represent the energies of God, and reflect the Divine Presence within creation.

2. Three Angels

The series of Angel figures that I worked on when I was in Germany, thinking about the ‘Spirit of the Place’ in the ancient ruin of the Cistercian abbey at Chorin, developed the idea that there is an angelic presence in a Holy Place. I have been very much impressed by the idea of the “Angel of History” that the German Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin spoke of, and which the artist Paul Klee tried to represent. So I decided to think about the Angel-presence in this ruined historic building, which was first constructed by monks from Citeaux, who had been invited to come to these “Marches of the Dukes of Brandenburg”, to start agriculture in a wild and forested area. In this image I was thinking of the three angels who came to visit Sarah and Abraham, and camped under the sacred oaks of ‘Mamre’. I used the architectural forms of the brick Minster, where we find a whole series of windows, that have intricate Mandala patterns made from local clay, and then fired. The Mandala form of the window represents the open heart of the angelic presence, which symbolizes the Trinity that is both the unity, and diversity to be found in nature.

3. Angel with Elijah

This is another picture of mine which was done in the early nineties, and was originally planned as a Tabernacle setting. Elijah, we are told, (1 Kings 19:5-9a) was deeply despondent, and in his sleep an angel appeared and laid a vessel of water beside him, along with some scones for him to eat, and then in the strength of that food he walked for forty nights and days until he reached Horeb, and there in a cave he heard the still small voice (I Kings 19:9b-16). That is a theme I have repeatedly returned to, as the image of the cave, as a place of receiving inspiration is close to the Indian tradition where we hear of the "Cave of the Heart". I have wondered if the angelic energies could also be related to moods which we have, which I feel can be transformed into ‘feelings for God.’ Monks in the desert often felt profound moods like depression, sorrow or anger. These moods are not just human impulses, but come to us through the whole of nature, and represent a deep connection which we have with the seasons, and the way in which nature also passes through different modes.In Indian aesthetics these are called Rasas, or essences, which inform our imaginative response to our human condition in this world. In fact one could even relate this to the different musical forms, that also evoke feelings which can be either joyful, or dark and despairing.

4. The Angel of vegetation

Over the last twenty years I have been particularly interested in what I have called ‘Primal Faith systems’, such as we find in the tribal cultures of India. I have been very much impressed by such powerful images that we see in pre-historic art forms, like in the caves of ‘Edakkal’ that are in the Wyanad district of South India, in North Kerala. These figures remind one of tribal art forms that we see among the Saora tribes of the East of India, or the Warli art of the West coast. I have made many sketches of these figures and from these sketches which are quite abstract, I created a series of Angel forms that represent for me the ‘Bhutas’, or spirits of the Earth, which tribal peoples in India believe in. These figures are like guardians of the vegetation, and later came into Buddhist art as the ‘Yakshas’, or presences that inhabit the sacred grove.

5. The Angel of Fire.

This image is part of the triptych of Angels that represent the Elements. It is similar in a way to the work I did on the Angel in the fiery furnace which we find in the book of Daniel, into which the three youths were thrown by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar. (The fiery furnace is a passage from the Book of Daniel (chapter 3). In a sense one could say that the Vedic gods like ‘Agni’ (the god of fire) were angelic forces, that are not only physical phenomena, but are deeply numinous presences. This was the idea of Owen Barfield in his book ‘Poetic Diction’, which was to very much influence people like C.S. Lewis and Tolkein. Dom. Bede Griffiths also refers to this in his book on the ‘Marriage of East and West’.

6. The Angel of water.

The Angel represented here is like the angel that we are told stirred the waters of the sacred pool of Bethesda which was associated with healing. There are many accounts of angels who are healing energies or energies of life present in water, especially wells or springs. I tried to show that this angel comes out of the stirring of water, rather like the installation by Bill Viola which was entitled : Five Angels for the Millennium, exhibited at the Tate Modern.

7. Apocalyptic angel

I have often wanted to paint a series of pictures on the book of the Apocalypse. In fact another series of Angels which I did was on the Angels of the Churches which Mary Lewis has in her home at Welsh Poole. This image is rather like a ‘Thankha’ tapestry with the angelic Person who could also be called the “Son of Man”, a term that is applied to Jesus. Muslims also have a whole very complex idea of Angel beings, some of whom are also thought to be satanic. This was probably because they were drawn from ancient tribal cosmologies, thought to be at variance with an Abrahamic faith in the One God. This picture was originally intended for a poster which was used during Advent.

8. The Angels of the storm

Deborah, one of the prophetesses of Israel sings a song of deliverance (Judges 5). Verses 3-11 link the giving of the Law at Sinai with the deliverance of the Israelites from the Canaanites. At Sinai, God made a covenant with Israel. But in the song of Deborah this deliverance is represented as a Cosmic event. The “stars” joined in the fight, doing battle against Sisera. Torrential rains turned the river Kishon into a raging flood.

They fought from heaven,

The stars in their courses.......

But they that love Him

Be as the sun going forth in its might.

I was very struck by a book written by Martin Buber on the Old Testament, where he discusses this ancient hymn of Deborah. As far as I can remember Buber links this hymn of deliverance to a psalm which speaks of the Lord riding on the Storm clouds. Of course it is an almost terrifying image of the God of Hosts, who does battle. In Psalm 18 we read :” He mounted the cherubim and flew; he soared on the wings of the wind”. It is this cosmic vision that underlies the way in which the Angels are represented in the Bible, I feel. And it is that cosmic vision of primordial forces that comes close to the myths that are so important in the Indian tradition.

Here this angel of the storm is above the holy mountain Shiva Ganga not far from where we live--perhaps you visited it. The gods of the storm are called the Maruths in India, and the image of the storm is very important in Indian thought, related I feel to the onset of the Monsoons.

9. A Trinity design for window.

This design was turned down, because the Tribal ‘Bhils’, for whom it was made, said it reminded them of the ‘Bhuthas’, or ghosts of the forest that they had left behind them when they became Christian. Eventually this cartoon was bought by a Canadian called Klaus Klostermaier who teaches comparative religions. I do feel that it is important that when visualizing the image of the Angel the figure is not just sweet and pretty. For me that is often what is most dissatisfying in the Angels that the Pre-Raphaelites like Burne Jones painted. The angels were awesome, and could inspire dread.

This does lead us to the question of ambiguity in the Angelic Beings. Lucifer, who carried the light, was also the source of darkness and evil. In Indian mythology we have the Asuras as opposed to the Devas--both represent elements of the divine energies present in Creation. By simply discounting the dark forces that we experience in the world around us, like rejecting the negative feelings we experience in anger or despair, we risk turning the world of the Angels into something that has no depth, and becomes only decorative.

10. Three Angels as Trimurthy

Going back to the Abbe Jules Monchanin, who was the first to found ‘Shantivanam Ashram’ as the “Sat Chit Ananda Ashram” dedicated to the Trinity, there has been an effort among Indian theologians to relate the concept of Trimurthy, which is particularly important in the Shaivite tradition, to the Christian understanding of Trinity. Monchanin spoke of India as being the land of the Trinity. Raimondo Panikkar wrote an important essay on the Trinity in the World Religions. Dom Bede Griffiths introduced me to this concept, and as a result I painted many images of the Trinity as Trimurthy over the years.

This picture is perhaps one of the first attempts I made, when I was with Dom Bede Griffiths in ‘Kurisumala Ashram’ in Kerala.The figures of Abraham

and Sarah are dressed in the Syrian Christian tradition.

11. The Angel of the forest.

This was done two years ago in Chorin, and represented the crucified angel in the primal forest. In a way this is like a Primal Person in the forest, who could also be a crucified Angel, like the one that St.Francis of Assisi had a vision of at Alverno,, and from whom he received the Stigmata. The Indian concept of the Primal Person or Adi Purusha, could be related to the Angel. Often a human being can be seen as an Angel, as St. Benedict suggests in his Rule for monks, where he says that we should offer hospitality to everyone, because on many occasions those whom we entertain, may in fact be angels in disguise. The line between the human and the angelic is not clear. In fact we can suggest that the Angelic Presence is where the human meets and interacts with the whole of Creation.

12. The Angel of fire.

This image of the Angel in the flames, was related to the red bricks of the Church which were fired by the monks using the trees which they cleared in order to do agriculture, and the very rich clay which is in that place, related to the ancient lakes that go back to the ice age. I think what I was particularly thinking of was the sacred place as almost an oven, or place where matter is being transformed. In the past I have done a number of pictures on the angelic persence that was in the great fire which was constructed to consume the three youths Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego (Daniel 3). I found that a story explaining the origin of the Indian ritual of ‘Arathi’, or the waving of a lamp before the mystery of the Divine darkness, also spoke of the Divine Presence which was sensed by the three great mystics of the Vaishnavite tradition who are known as the Alvars. This mystery of the fourth Being, which is the Divine presence who comes to join those who are his true believers, is perhaps behind the idea that where “two or three are gathered together in my name, I am there in their midst.” This idea of the Angel that is present in the community of believers, could also explain the “Angels of the Chrurch’s” which we find described in the Book of Revelations.(Revelation 1:11)

13. Angels of the past.

As I mentioned earlier, the idea of Walter Benjamin concerning the “Angel of History” which looks both forward and backwards, has inspired me. According to Walter Benjamin, “This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward.” It is this vision of history as determined by angelic forces that the artist Paul Klee represented in his 1920 painting Angelus Novus.

Here in this picture of mine, I wanted to represent the presences that I felt particularly in the inner space of the ruined monastic Minster at Chorin. Here I felt that the angels were almost like the spirits of the ancient monks who had chanted there. In a way the monastic tradition arose from an idea that to be a contemplative monk was like living the angelic life here on earth. The angels are contemplative presences around the throne of God. They are always overshadowing, so to say, the Holy place, as in the Temple that Solomon built, where angels were represented as enclosing, or covering the Tabernacle, or the place of reconciliation between God an the human community. The Holy of Holies is the place of the Angelic presences.

14. Angel of Ecology.

This is another of the series of Angels that I worked on in Chorin.

There were many lakes in that area, and the place has become very much concerned with ecology. So I thought of a kind of green man who is also an angel. Here the heart of the angel is related to the waters. I also related the idea of the angel to the ruin. Owen Barfield in his book on ‘Poetic Diction’ devotes a whole section to the Ruin. He says that the word derives from an ancient root which means something flowing like water, that is constantly in a state of flux, and changing. Earlier, I had done angels related to the elements. In fact I had thought that one could see the three angels Gabriele, Raphael and Michael as very close to Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. The Angels in the Biblical tradition were ancient Canaanite gods who were absorbed into the mythic world of the Hebrew peoples.

15. Angel of the Landscape.

I have represented Angels as part of my interest in the landscape. In the image of the three Angels as part of an Indian landscape, with a Banyan tree, and again a mountain from which is flowing a stream of water, I was thinking of the whole landscape as filled in a way with angelic forms. I suppose that some people might feel that this is an almost pantheistic way of understanding the angelic as the inner spiritual dimension of nature. But as I have tried to suggest, what I am hoping to express through my art is what some theologians have called a ‘panentheism’ which is also a Cosmic world view that goes beyond nature as we experience it around us, to encompass a universal vision that includes the whole of creation as being in a way the “Body of God.”

.jpg)

.jpg)